The Age of Epistemic Decoupling: Mimicry as Architecture, Simulation Without Sovereignty

Symptoms

The Performance of Thinking

You step into the room. The room is familiar. It is large, air-conditioned, carefully lit, polished into seriousness with leather and wood furniture. The chairs are heavy and upholstered, the coffee imported. The speaker often a minister, an executive, a high-ranking official stands confidently at the front. He is articulate, well-dressed, networked, fluent in the language of modernity. The vocabulary flows easily: “ecosystem,” “KPIs,” “AI and Innovation,” “global competitiveness,” and “transformation.”

At first glance, it all feels convincing. These are educated people trained abroad, featured on panels, celebrated in international circles. They speak the language of reports and global frameworks, referencing buzzwords from strategy decks and popular thought leadership books. Everyone in the room knows what to say and more importantly, what to signal. Language becomes a currency, traded to show you belong.

But sit long enough—really sit—and something begins to feel off. You try to follow the logic, but it slips. The ideas, while individually polished, do not add up to thought. They are fragments, recycled metaphors, gestural nods toward vision. There is no slow build, no inquiry, no pause to consider:

What does this mean?

Where does it come from?

For whom is it being built?

The conversation glides on surfaces, circling itself. Concepts seem lifted, not lived. You squint. And slowly, a disquieting realization emerges: this is not a space for thinking. It is a space for coordinated signaling. The people are not dishonest in any malicious sense. In fact, many of them believe they are thinking. But what they are performing is the gesture of thought: confusing execution for reflection, and project management for philosophy. Scheming becomes planning. Branding becomes strategy. The forms of thinking are replicated, its rhythms, its lingo, its deliverables, but the interior is hollow. This is what Baudrillard (Easthope, 1998, pp. 341–343) called a simulacrum: a space where signs and performances replace substance … a performance of intelligence with no ontology behind it.

You begin to see the structure behind the words. What is called a “program” may be no more than a WhatsApp group with a logo. An “initiative” is often just a press release timed to a media cycle. A “campaign” might be a PowerPoint deck translated last minute from a consultancy’s archive. There is no deception, because there is no interior from which to deceive. As Gertrude Stein once wrote: there is no there there.

And this isn’t about failure. It’s not the incompetence of individuals. The budgets exist. The staff are present. The consultants deliver on time. The media covers the launch. But when you step back, it becomes clear: this isn’t dysfunction. It is design.

The design selects for safety. It favors speed, optics, control. It elevates ideas that have already been validated by global policy circuits. Ideas that are branded, digestible, proven market-ready. They might be written in Arabic, but they are English in worldview: stripped of ambiguity, scrubbed of resistance, designed to perform well on a stage. There is no room for philosophical grounding as it is too slow. No space for ontological questioning as it breaks the mood. Discovery becomes a liability. Long-term infrastructure becomes “not feasible.” Reflection is inefficiency. The system selects for what can be launched fast, marketed well, and celebrated in a forum.

What we are seeing, then, is not just bureaucracy or branding. It is a knowledge infrastructure optimised to simulate intelligence while disabling thought. Institutions that look functional, ministries, think tanks, digital labs, academic boards, but are hollowed out by mimicry. Forms that resemble knowledge-making without the risks or responsibilities of actual knowledge. It is what Bhabha (1994, p. 86) described as mimicry, not exact copying, but an “almost the same, but not quite,” where institutional surfaces appear modern, but lack epistemic sovereignty.

Once you see this, it cannot be unseen. The pattern begins to repeat: across ministries, authorities, research councils, startup accelerators, “vision” documents. Strategic directions with no philosophical base. Policy platforms built on borrowed idioms. Pilot projects that perform innovation without asking what innovation is for. Institutions that look modern, but possess no sovereignty of mind.

And there is a particular kind of violence in this. It is not loud. It does not announce itself. It comes not with boots or chains, but with task forces and executive roundtables. But its violence is interior. It hollows cultures from within. It punishes epistemic friction. It isolates those who ask real questions. It drives the independent mind to silent accommodation or quiet exile. Over time, a fog sets in. Cultures forget what they once knew how to ask. A generation grows up in rooms that resemble intelligence, but do not generate it. But as designer and scholar Tristan Schultz reminds us, “It is not enough to decolonize institutions at the level of aesthetics or access. The work must be ontological” (Schultz, 2018, p. 6). The critique here is not merely functional. It is about the epistemic foundations on which these systems are built or rather, not built. Institutions simulate the outer shell of intelligence without asking what knowledge is, or where it comes from. The result is a crisis not just of outputs, but of orientation.

This isn’t simply about poor leadership or short-sighted management. It is deeper. It is civilisational. A structural evacuation of thought and the normalisation of its simulation.

2. Mechanisms

How does this happen? What keeps it going?

Once you begin to recognise the pattern, you might ask: if the minds are smart, the budgets generous, the institutions well-structured … what explains the hollowness? Why do rooms full of qualified people produce such thin thinking?

A large part of the answer lies in the design of institutional culture itself. In many modern bureaucracies especially those modeled after Western development templates the goal is not to think, but to appear thoughtful. Success is measured not in coherence or inquiry, but in alignment with language trends. And so entire systems form around fluency: in PowerPoint, in English idioms, in global development lingo. Mastering the rhythm of speech becomes more important than generating insight. This creates what might be called a simulacrum of thoughtfulness, where thought is performed convincingly, but never undertaken. It looks like thinking, it sounds like innovation, but it is neither. As Herzfeld (1983, p. 166) describes in his analysis of rural Greek moral systems, this is a form of "semantic slippage"—where words retain their authority even as their meanings dissolve. Institutions invoke terms that once carried weight, but now function as hollow signifiers, maintaining control through familiarity rather than substance.

Inside this architecture, people rarely speak from a place of situated understanding. They speak from decks, from strategies, from recycled roadmaps. Often, these documents are not even their own: they are imported from consultants, sometimes copied from a neighbouring ministry, occasionally mistranslated. There is no time to reflect or adapt. Because the system doesn’t reward depth, it rewards momentum. It wants ideas that can be launched, not examined. Ideas that signal modernity, not wisdom. In such a system, discovery becomes a liability. To not know — and to say so — risks being seen as unprepared. So everyone appears certain, even when nothing is being said.

The deeper structure here is that of the technocratic echo chamber: an institutional culture where only certain kinds of speech are permissible the measurable, the managerial, the motivational. Leaders are expected to act like consultants; thinkers are expected to present like marketers. But no one is expected to interrupt the assumptions underneath. Questions like “What is knowledge for?” or “Who defines success?” or “What future are we building?” are seen not as necessary, but inconvenient … slowing down timelines, making deliverables ambiguous. So they’re quietly dropped from the agenda. In time, the ability to ask such questions withers. Institutions lose the muscle for philosophical interruption.

Worse, these hollow performances are often elevated to the level of national progress. Leaders begin to associate success with visibility: media appearances, international panels, branded initiatives. Knowledge is no longer something to pursue, it is something to stage. The system evolves into what we might call a PR epistemology: an arrangement in which knowledge production is judged by how it looks from the outside, not whether it answers anything real. When the highest praise a project receives is “this would make a great story for the press release,” you’re not building a knowledge system … you’re designing an illusion.

This performance culture is not just local. In fact, it’s deeply global. Many of the metrics and frameworks being mimicked were never designed to foster indigenous thought. They emerged in a different civilisational context, with different goals and values. And yet, they are imported wholesale: institutions replicate the forms of research centres, innovation hubs, foresight labs, without confronting the epistemic frameworks that gave these forms coherence in their place of origin. The term “mimicry” is used here not only in its postcolonial sense, as in Bhabha’s analysis of mimicry as “almost the same, but not quite” (Easthope, 1998, p. 7), but also in a structural sense: a replication of forms stripped of their grounding logic. What results is a “colonial epistemic hangover,” a term this essay reworks beyond its conventional usage to describe an institutional condition in which the structure of modernity is copied, but the ontological foundations are ignored.

In such a landscape, philosophy becomes a threat. To question is to delay. To reflect is to risk looking inefficient. And so institutions optimise for speed, scale, and sparkle favouring what can be built quickly, evaluated easily, and praised internationally. The long, slow projects, the ones that don’t produce flashy outputs, but root knowledge in local soi, are dismissed. Not because anyone is hostile to meaning. But because meaning is unprofitable. It doesn’t trend.

What results is a deep and dangerous civilisational responsibility gap. Institutions claim to represent knowledge, culture, education, future-building, but they do so without anchoring in the responsibilities those missions require. They have vision, but no worldview. They issue strategies, but cannot answer for them. They inherit roles once held by elders, scholars, philosophers, but speak only in slogans. And when it all collapses, there’s nothing to fall back on. No roots. No memory. Just the aftermath of simulated progress.

This, then, is the mechanism: a system of surfaces, echoing expertise, optimised for speed and spectacle, unmoored from purpose. It does not lie, but it cannot think. It performs knowledge, but cannot carry its weight. It speaks of the future, but does not know where it is going.

Roots

Where does this come from? Why does it persist?

By now, the symptoms are familiar: the polished performance, the empty language, the systems that reward momentum over meaning. But these are not just accidental outcomes of weak leadership or global trends. They emerge from something deeper … a long, layered history of displacement. Not of people, but of ways of knowing.

The modern institutional world that many countries now inhabit, particularly in the Gulf and wider Arab region, was not built from within their own epistemologies. It arrived pre-assembled. Postcolonial states inherited institutional blueprints drawn from foreign civilisational models: British bureaucracies, French ministries, American think tanks. These were not adapted, they were mimicked. Their form was embraced, but their function, their philosophical foundations, their cultural justifications, were often never interrogated. And so, over time, a subtle kind of amnesia set in not just about what to think, but how. As Edward Said noted, “There has been no major revolution in the West’s perception of the Orient…” (Said, 1978, p. 273). In this context, it is not only the West’s perception that persists, but the self-perception of former colonies, who internalise and replicate those inherited frameworks without radical transformation.

As Tristan Schultz argues, this is not just historical residue, but an active and ongoing form of “epistemological dispossession,” where entire populations are dislocated from their capacity to generate meaning from their own worldviews (Schultz, 2018, p. 7). The design templates imposed from abroad come not only with architectural blueprints, but with ontologies embedded in their structure. When these forms are copied without their metaphysical basis, they result in institutional incoherence.

In this amnesia, the idea of knowledge itself began to shift. It was no longer ‘ilm rooted in responsibility, revelation, and the ethical pursuit of truth. It became “information,” “output,” “intellectual property.” Wisdom traditions that once connected knowledge to the soul, the city, and the cosmos were quietly replaced by management theories, KPIs, and innovation frameworks. These new languages were not evil. But they were not neutral either. They carried within them the cosmologies of the worlds that produced them. And when these worlds were copied — without reflection — the result was not hybridity, but hollowness. George Saliba (1999) reminds us that the Islamic scientific tradition was once deeply integrated with metaphysical inquiry “mathematics, astronomy, and cosmology” were part of a larger ontological project (Saliba, 1999, p. 12). When knowledge is severed from that metaphysical anchoring, it becomes technocratic: instrumental, but no longer civilisational.

This is the quiet tragedy of the colonial epistemic hangover. It does not shout. It whispers. It tells people that progress means looking modern. That authority is gained by citing Harvard, not Ibn Sina. That to be “world-class,” one must speak with an accent, design with Helvetica, and use concepts that have already been validated in Geneva or Palo Alto. In this way, entire generations are taught to simulate Western styles of knowledge without asking:

what was displaced to make this possible?

Some describe this as modernisation. Others call it global competitiveness. But at its core, it is mimicry not as a strategy, but as an ontological default. The institutions do not just adopt Western tools they absorb its anxieties, its aesthetics, its belief that speed equals intelligence. This internalised calibration of value — where proximity to foreign form becomes the measure of worth is not new. As Fanon wrote, “The colonised is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country’s cultural standards.” (Fanon, 1986, p. 18). This mimetic logic still organises institutional behaviour today. And when these borrowed tools fail to answer local questions, the institutions do not look inward. They look further abroad. For another toolkit. Another model. Another external savior.

Kennedy (1983) shows how even in technical domains like geography, Islamic knowledge was embedded in ethical and theological commitments, not reduced to data or projection (Kennedy, 1983, p. 28). The loss of this epistemic integration explains why modern frameworks feel disconnected, they pursue precision without purpose. And so, the mimicry deepens. A mimetic bureaucracy takes root, one that knows how to produce slides and strategies, but no longer knows how to sit with doubt. No longer knows how to ask questions without answers. No longer remembers that to build anything real, you must begin not with optics, but with ontology.

But mimicry alone doesn’t explain why this persists. For that, we must look to fear. The fear of appearing unmodern. The fear of being judged by external funders or international observers. The fear of looking backward. These fears are not irrational. They are the residue of histories in which people were told — explicitly or implicitly — that their own knowledge systems were inferior. That to modernise meant to shed their own traditions, to become interpreters of someone else’s ideas. This class of interpreters, as Tlostanova (2015) explains often rises to prominence not by producing new knowledge, but by acting as “transmission lines” between local contexts and Western expectations (Tlostanova, 2015, p. 72). They become the native informants of global policy, tasked with explaining their culture in terms the dominant world can understand.

And so, to question now feels dangerous. To slow down feels like betrayal. To think from within one’s own worldview feels almost… rebellious. This is the deeper violence of intellectual colonisation. It does not just erase ideas. It trains people to doubt the soil from which their ideas might grow. What remains is a system that cannot stop moving because stillness would require memory. And memory might provoke reckoning. And reckoning might require repair.

CONSEQUENCES

The Price of Simulation | What Follows the Performance

It doesn’t begin with failure. It begins with fluency. A report gets published. A lab is launched. A vision is declared. The rooms are full, the slides are sharp, the applause is warm. Everything seems to be working. And in a way, it is. But sit with it long enough, and a quieter story begins to surface. A designer who feels displaced in her own visual culture. A strategist who can recite global metrics, but no longer knows what they mean. A professor who teaches critical thinking, but can’t remember the last time she was allowed to question a framework.

No one calls it a crisis. The systems keep running. The outputs keep coming. But underneath the performance, something is drifting. Institutions built to think begin to simulate thought. Cultures that once generated meaning begin to echo someone else’s language. Individuals fluent in execution begin to lose access to their own clarity.

This isn’t the drama of collapse. It’s the ache of erosion. The slow fading of epistemic gravity. A society that becomes excellent at planning, but forgets how to orient. That builds beautifully, but cannot remember why. That innovates constantly, but no longer knows in which direction. What follows are not abstract categories. They are lived conditions. They unfold across institutions, across cultures, across inner lives. They stretch across time, from memory to vision, and accumulate slowly, until disorientation becomes normal. What follows are the consequences.

I. Structural Consequences (Macro)

System-Level Fractures

It begins at the top—inside the systems built to plan, predict, decide. Ministries, think tanks, foresight labs. At first glance, they appear functional. The architecture is modern. The reports are published on time. The meetings run smoothly. But over time, a strange pattern emerges. These institutions are filled with motion, but resistant to contradiction. Ideas are welcomed, as long as they don’t interrupt. Policy shifts are announced, as long as they don’t unsettle. Dissent is tolerated, but only as performance. Beneath the busy surface, a deeper erosion takes place. The capacity for internal tension begins to fade. Philosophical pressure is treated like interference. The result is not chaos. It’s coherence without depth. A structure that looks intelligent, but cannot hold paradox. A surface that simulates thought, but cannot metabolise contradiction. (Baudrillard, 1994, p. 6)

Simulacrum Thinking

Inside these spaces, a specific rhythm takes hold. It’s fast, articulate, self-assured. You hear talk of frameworks, decks, ecosystems. The language of global consultancy, dressed in national colour. You realise quickly: the aesthetic of thought is everywhere. Intelligence is evoked in symbols, white papers, executive briefings, pilot programs, but rarely in process. The forms are familiar, the gestures precise. But there is no grounding. No interiority. What’s being performed is not thinking, but its visual mimic, what might be called simulacrum thinking. (Baudrillard, 1994, pp. 3–4) The institution appears modern. It references all the right theories. But the thinking inside is not slow, not situated, not sovereign. It is coordinated resemblance. It is intelligence without weight.

Collapse of Intellectual Metabolism

The pace is impressive. A new strategy every year. An innovation unit for every sector. Ideas move fast, sometimes too fast to land. You watch as reports are published before they’re read, and decisions made before they’re questioned. Concepts circulate, but nothing stays long enough to shape behaviour. There is no absorption. No digestion. Insight arrives, gets formatted, and moves on. The system is in motion, but not in reflection. What emerges is a kind of epistemic anemia. Intelligence becomes surface-level. And slowly, the deeper faculties of thinking, rumination, contemplation, ethical orientation, begin to dull. This is the collapse of intellectual metabolism. The machinery of thought remains. But its organs have atrophied. (Escobar, 2018, p. 114)

Weaponised Research

Research is still present. In fact, it’s everywhere, commissioned studies, evaluation reports, baseline assessments. But the function has changed. It no longer points toward discovery. It points toward justification. Research is now deployed to validate choices already made. It lends credibility, not inquiry. It is performed to satisfy funders, not to provoke new directions. You hear, “We’ve done the research,” and understand: the answer was chosen first. The study followed. This is weaponised research, not in the sense of aggression, but of instrumentalisation. Research that shields decisions instead of guiding them. Intelligence that protects the system from discomfort. (Tlostanova, 2015, p. 60)

Technocratic Echo Chambers

Over time, a specific language begins to dominate. It is clean, confident, free of ambiguity. Words like “feasibility,” “impact,” “alignment,” “efficiency.” The cadence is managerial. The mood is motivational. But something essential is missing. No one speaks from philosophy. No one brings the ethical into the room unless it’s quantified. Words like justice, memory, cosmology—if they arrive at all—arrive as metaphors, not mandates. Anything that cannot be measured is treated as indulgent.

Over time, this becomes the boundary of institutional discourse. The system begins to echo itself. A language optimised for consensus, not depth. This is the formation of technocratic echo chambers rooms that speak fluently, but only in the register of control. Anything that resists calibration is quietly excluded. Not punished. Just ignored. (Schultz, 2017, p. 33) And so, institutions that were meant to build the future become unable to imagine it. They remain full of activity, full of deliverables, full of plans. But step back, and you see the pattern: every initiative loops back to itself. The form holds. But the center is missing.

II. Cultural & Sectoral Consequences (Meso)

Mimicry Without Memory

It begins subtly. A logo redesigned abroad. A strategy document modeled on a European framework. A curriculum adjusted to mirror a top-ranking school in California. Nothing feels wrong at first. In fact, it all seems promising. The visuals are sleek. The methods are standardised. The benchmarks are international. But over time, the alignment becomes dislocation. The symbols no longer speak to the stories beneath them. The methods no longer emerge from the soil they operate on. You start to see the outlines of mimicry without memory, a culture that copies the forms of others while forgetting its own foundations. The buildings are built with confidence, but lack lineage. The national brand looks globally competitive, but carries no cosmology. Identity is constructed, but not inherited. It becomes possible to describe a culture’s value without ever standing inside it. (Kennedy, 1987, pp. 15–16)

Narrative Amnesia

You walk into a museum. The lighting is perfect. The exhibit text is in three languages. There is a quote from a 10th-century thinker, elegantly displayed on the wall. But the silence around it is loud. No one discusses the context. No one traces the lineage. No one asks what it still demands of us. Heritage is present, but only in fragments. Culture becomes content. In public institutions, the same pattern repeats. An ancient proverb is included at the start of a report, then quickly forgotten. A historical reference is used to validate a program, but not to shape it. These gestures are not malicious. But over time, they produce narrative amnesia. The past is referenced, but not remembered. The stories survive, but the storytellers are gone. (Escobar, 2015, p. 453)

Design Pedagogy as Export Simulation

In classrooms, a different tension unfolds. The slides are sharp. The terminology flows. Students can map a stakeholder journey or critique a user interface. But when you ask them to design from within their own visual tradition, the room goes quiet. It’s not that they don’t want to, it’s that they were never asked to. The references are all foreign. The critiques are all external. Design education becomes fluent in frameworks, but estranged from worldview. This is not just a gap in content, it is a deeper displacement. Students are taught how to think creatively, but not where that creativity comes from. They learn how to solve problems, but not how to define them. Over time, what emerges is design pedagogy as export simulation, a training ground for translation, not generation. Knowledge arrives pre-packaged. The origin story is never theirs. (Ansari et al., 2019, p. 124)

Temporal DislocationAt conferences, the past is quoted. In policies, the present is polished. In strategies, the future is predicted. But something feels disconnected. The past is celebrated selectively, usually when it fits a clean narrative. The present is sped up—optimised for optics. The future is projected using borrowed metaphors, mapped in imported language. You begin to feel the ache of temporal dislocation. A timeline where memory is aestheticised, the present is managed like a startup, and the future is branded for visibility. What’s lost is continuity. A society starts to drift, not because it forgets, but because it doesn’t know how to hold its own time. (Schultz, 2017, p. 30)

Ontological Opposition

And then there is the tension that goes unnamed, but never unnoticed. A young architect tries to bring in local material. She’s told it’s nostalgic. A historian suggests rethinking a project through indigenous cosmology. She’s told it’s not scalable. A policymaker references stories from the land, only to be met with polite silence. Over time, the message becomes clear: what is rooted is seen as regressive. What is remembered is seen as inefficient. Attempts to ground design in story, land, or soul are not rejected outright, they are simply not invited back. This is the quiet operation of ontological opposition. Heritage is treated as heaviness. Memory as delay. Ambiguity as threat.

And so, the built environment follows suit. A park looks beautiful on a drone shot, but ignores wind. A cultural district feels modern, but disorients the body. A masterplan is award-winning, but no one wants to linger there. The land begins to reflect the logic of the system: structured, impressive, but airless. A landscape that can no longer breathe. (Escobar, 2018, p. 9)

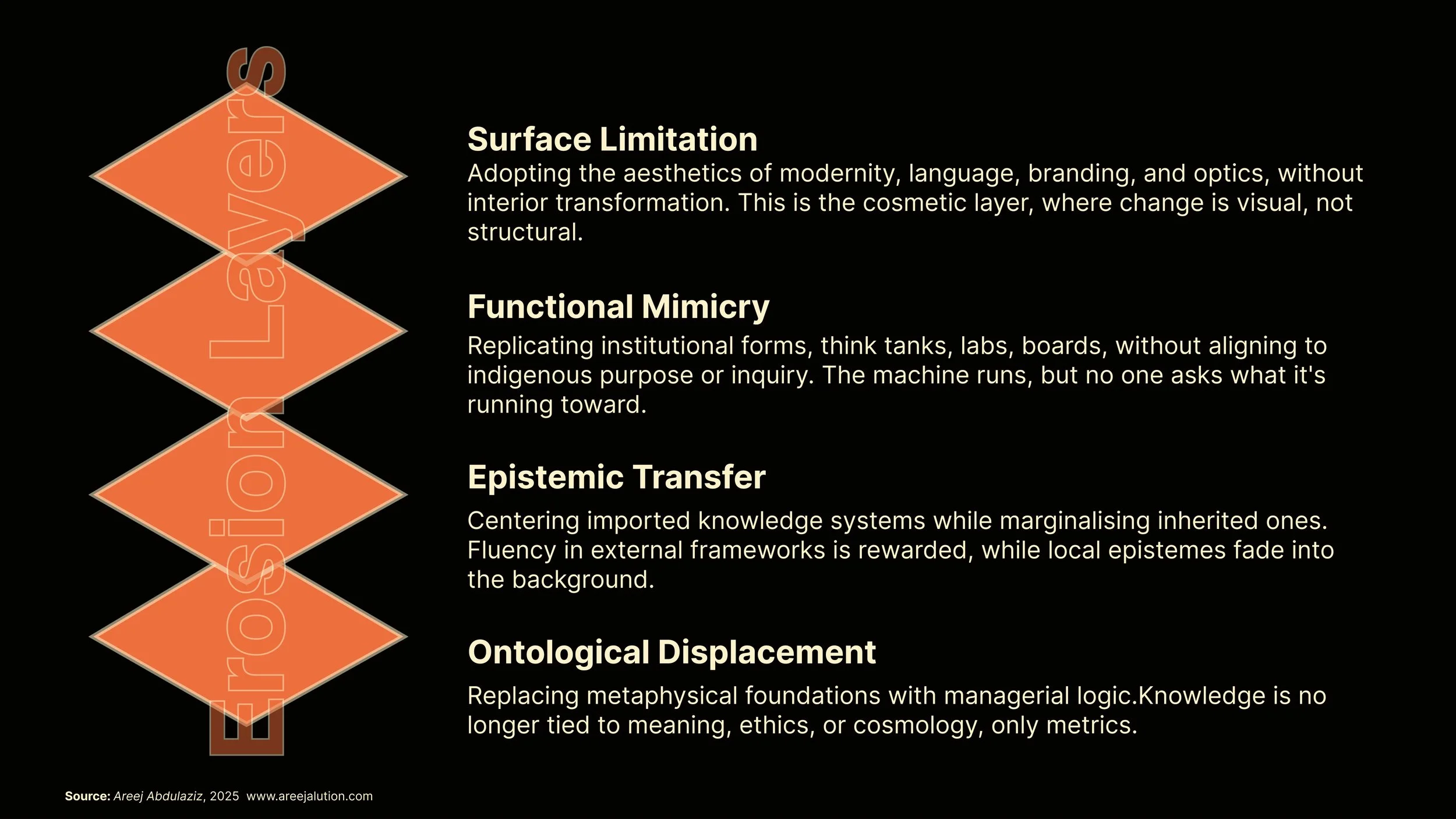

The Erosion Layers

This erosion operates in layers, some visible, others structural, and some deeply ontological. Each layer compounds the disconnect between the outer form of modernity and the inner weight of meaning.

III. Interior Consequences (Micro)

Erosion of Inner Clarity

It starts quietly. Not with exile. Not with confrontation. Just a subtle drifting … between what you know and what you must say. You prepare the strategy deck. You translate the framework. You align your words with what the room expects. And you tell yourself: it’s fine. It’s just a job.

But something shifts. You stop asking your own questions. You stop lingering on doubt. You begin to speak in borrowed rhythms, think in borrowed categories, dream in borrowed futures. The system doesn’t silence you. It simply never asks for your voice.

Over time, the interior begins to blur. What once felt clear becomes difficult to access. Your thoughts start to pre-edit themselves. You become good at adapting. Good at sounding smart. Good at performing coherence. But the ground beneath you is thinning. This is the erosion of inner clarity, not the loss of intelligence, but the quiet departure of alignment. You still speak. But it no longer feels like it’s from within. (Tlostanova, 2015, p. 44)

Ontological Misfit

Eventually, someone notices. Not because you failed, but because you didn’t. You arrived with integrity. You spoke from conviction. You refused to fragment. You asked why, when everyone else had moved on. And the system didn’t punish you directly. It simply began to shift its tone. You were told you were “too principled,” “too intense,” “not strategic.” You were moved off the core project. You were left out of the next meeting. And then, finally, you were thanked and quietly removed. This is the condition of ontological misfit. You did not resist. You simply refused to perform without meaning. And that made you incompatible. Not because you were wrong, but because you were real. Your presence made the simulation harder to sustain. (Schultz et al., 2018, p. 6)

Epistemic Fracture

Some adapt. They learn how to switch codes. To say the right thing, even when it feels hollow. To lead with confidence, even when they feel disoriented. Over time, this becomes second nature. The exterior looks successful. But inside, something is split. You speak in one voice, but think in another. You move through institutions, but feel like you’re watching from outside. You grow fluent in reports, metrics, and models, but none of them belong to you. This is the onset of epistemic fracture. The split between outer fluency and inner silence. A quiet dissonance that deepens with every promotion. (Baudrillard, 1994, pp. 6–7)

Spiritual Erosion

At first, you don’t notice. You’re too busy. Too embedded. Too rewarded. But then, in the in-between moments, on the drive home, in a quiet prayer, in a conversation with someone who remembers, you feel it: a loss of weight. A thinning of clarity. A doubt, not about your work, but about yourself.

Fitrah, the innate sense of alignment, used to guide you. Now it’s harder to hear. The instincts that once felt sharp begin to dull. You learn to override them. To smile. To adjust. To stay.

This is spiritual erosion. Not the loss of faith, but the fading of inner guidance. A kind of forgetting, not just of content, but of center. Some live with it. Some numb it. Some leave. And some simply vanish from themselves, staying in the system but no longer in the room.

Across generations, this becomes normal. The most competent are seen as difficult. The most thoughtful are called slow. The most grounded are framed as backwards. And a new archetype emerges: fluent, efficient, visionary, but floating. Leaders who can articulate ambition, but not orientation. Professionals who can manage projects, but not meaning.

What’s left is a class of people trained to move systems forward, but unable to ask: forward into what?

Temporal Consequences

PAST: Museumisation of Meaning

You walk through a gallery. The tiles are clean. The script is elegant. A scholar’s words are carved into the wall—illuminated, framed, quoted. But no one is reading to understand. The past is present, but only as ornament. It has been placed behind glass. You are invited to admire it, not inherit it. In ministries and universities, the pattern repeats. Islamic knowledge is referenced in mission statements, but absent from decision rooms. Heritage is celebrated in brochures, but not embedded in pedagogy. The canon is preserved, but disconnected from practice.

This is the museumisation of meaning. As Escobar (2015, p. 453) argues, development often functions by “suppressing other ways of knowing and being in the world.” The past becomes safe only when disarmed of its epistemic demands. Memory becomes something to display, not something to live from. It’s respectable. It’s even photogenic. But it no longer instructs. It no longer provokes. It no longer guides.

PRESENT: Ontological Friction

In the present, everything moves. A new initiative is announced. A rebrand is launched. A digital platform is introduced. Momentum is constant, but coherence is slipping. Inside institutions, people feel the tension. They’re asked to make ethical decisions, but within parameters that don’t allow for real ethics. They’re told to “think critically,” but within formats that reject complexity. The values are printed on the wall, but punished in practice.

This is ontological friction, the lived dissonance between what is claimed and what is possible. It reflects what Ansari et al. (2019, p. 124) describe as “disembedding design from its ontological contexts,” leaving behind only appearances. The pressure is not always external. Often, it is internal, a constant negotiation between personal integrity and professional survival.

FUTURE: Artificial Futurism

The future is everywhere. Vision documents. 2040 plans. Innovation dashboards. It is modeled, forecasted, stylised. Diagrams of progress are shared at summits. Scenarios are mapped. KPIs are aligned. But when you listen closely, something feels off. The futures being imagined do not emerge from within. They are modeled elsewhere, then imported. They come dressed in the language of possibility, but they do not carry the risks, questions, or ambiguities of real visioning.

This is artificial futurism. A projection of futures that feel inevitable, but lack intimacy. Baudrillard (1994, p. 6) warned of such simulations, where the representation of the future precedes and replaces the real, becoming a self-fulfilling illusion. The timelines are smooth. The goals are glossy. But the epistemic center is missing. There is no soil, no story, no sovereign metaphor. When pressure comes—climate, economy, ethics—the projection falters. Not because it failed. But because it was never rooted.

The Salt Castle Effect

Simulated Sovereignty

From a distance, it looks solid. The institution has a name. A mandate. A budget. The website is live. The leadership is confident. There are photos from conferences, quotes from global figures, accolades from international partners. It looks real. It looks ready. But then pressure comes: a social crisis, a moral dilemma, a need for reorientation and the structure buckles. Not with noise. Not with scandal. Just quietly, at the seams. Decisions can’t be made. No one takes responsibility. The language falters. The institution stalls. You realise: it was never designed to carry weight. There were no roots to return to. No memory to metabolise shock. The structure wasn’t empty. It was brittle.

This is the Salt Castle Effect, a term that echoes, but diverges from, AbdulRahman Munif’s haunting metaphor in Cities of Salt. In a 1986 interview, Munif explained the idea behind the title: cities that offer no sustainable existence. When the waters come in, the first waves will dissolve the salt and reduce these great glass cities to dust.

In Baudrillard’s terms, these are hyperreal institutions—copies without originals—propped up by symbolism rather than substance (1994, p. 1). They are not only fragile in function. They are hollow in form. These are not just places built on fragile ground, but systems of thought, governance, and design built without metaphysical anchoring .It’s not that people weren’t working. They were. Reports were written. Decks were refined. Panels were convened. But all of it looped—activity without orientation. Thought without interiority. Progress without becoming. And so the structure, like salt, holds its shape until pressure arrives. And when it does, it dissolves. Not because it was weak. But because it was never meant to last.

This is civilisational senescence a concept that captures aging without maturing, movement without memory (Baudrillard, 1994, pp. 97–99). The outward form continues. The inner vitality recedes. Institutions keep speaking, but forget what they were meant to say. Strategies multiply, but direction is lost. The tragedy is not that these systems failed. It’s that they succeeded at simulation. They created the conditions for motion, without movement. For visibility, without vision.

And so, what was meant to be progress becomes drift. What was designed to lead becomes a loop. What was imagined as future becomes glass—clear, polished, and dissolvable.

Reorientation

From Simulation to Sovereignty

It begins with a discomfort. A pause. A question that lingers a little too long. Someone asks not what the metric is, but what the meaning is. Someone else wonders aloud why the word futures no longer feels like a proposition, but a product. A young architect speaks of longing, and the room shifts uncomfortably.

This is not rebellion. It is remembrance.

Because once the hollowness is felt, even if quietly, it cannot be unfelt. What used to pass unnoticed, an imported framework, a strategy with no soul, a vision written in someone else’s metaphors, begins to lose its glow. The simulation thins. The glass starts to shimmer. The applause feels distant.

And something inside begins to stir. Not against modernity. But toward a deeper one. One where method and meaning are no longer split … where time, cosmology, and cognition can rejoin. This is the beginning of reorientation, not as return, but as rejoining. Not nostalgia, but cosmological repair (Escobar, 2015, p. 17). A refusal to accept that speed is wisdom, that metrics are truth, or that design is merely the arrangement of surfaces. In Arabic and Islamic traditions, to build is never just to construct …it is to align. It is to gesture toward a horizon greater than the form itself (Saliba, 1999, p. 10) .

Reorientation asks different questions. It does not ask, What can we launch quickly?

It asks, What does this help us become?

It does not seek louder outputs. It seeks softer grounds. It begins, often, in the margins. A designer asks why her curriculum contains no texts in her own language. A civil servant, trained to manage strategy decks, begins to feel the ache of disconnection. A researcher, fluent in global indicators, starts to long for something she cannot name. These are not inefficiencies. They are thresholds.

And there are people who have not forgotten. Elders who hold memory in silence. Teachers who still see geometry as theology (Saliba, 1999, p. 21) Communities who design not for disruption, but for direction. What they offer is not a toolkit.

It is a way of seeing.

A way of seeding.

A way of placing one’s work within an unfolding cosmology, not for display, but for devotion.

This is not about designing new models. It is about designing from a different center.

“We do not build domes to cover. We build them to echo the cosmos.” Areej Abdulaziz This is the shift. From architecture as enclosure to architecture as alignment. From metrics as validation to meaning as gravity. To reorient is not to reject tools, but to ask what worldview they serve. It is not to abandon systems, but to demand they carry soul. It is not to erase the modern, but to remember that other modernities exist (Tlostanova, 2015, p. 9). That our traditions held speculative futures long before they were named that in design studios (Escobar, 2015, p. 18). That the mihrab was always a futurist form, not pointing to the past, but opening a path (Kennedy, 1999, pp. 27–30) .

Reorientation is slow.

It is not disruptive. It is devotional.

It is a form of care, not just critique.

A re-coupling of responsibility and knowledge, of pattern and prayer, of space and story.

It asks not for scaling, but for stillness.

Not for trends, but for texture.

Because only roots can grow futures.

And when the root is forgotten, no amount of innovation can produce fruit.

To design from sovereignty is not to isolate. It is to integrate. To speak from one’s cosmology, not against others, but from the dignity of grounded voice. The prayer carpet does not erase the world. It orients the body within it. And this, too, is what reorientation offers: not an answer, but a direction. A way to step again into the work, with clarity, with rhythm, with reverence.

References

Ansari, A., Mayorga, A., Akama, Y. and Vyas, D., 2019. Decolonising design pedagogy. Design Issues, 35(2), pp.112–128.

Baudrillard, J., 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by S.F. Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bhabha, H.K., 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Easthope, A., 1998. Literary into Cultural Studies. London: Routledge.

Escobar, A., 2015. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Escobar, A., 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fanon, F., 1986. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by C.L. Markmann. London: Pluto Press.

Herzfeld, M., 1983. The Meaning of Ethics: Cultural Constructions of Moral Discourse, and the Comparative Method. American Anthropologist, 85(1), pp. 63–83.

Kennedy, H., 1983. Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. London: Longman.

Munif, A., 1986. Cities of Salt. Interview cited in Al-Azm, S., 2016. Arab Critique of Arab Oil Modernity. Beirut: Dar al-Fikr al-Arabi.

Said, E.W., 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Saliba, G., 1999. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schultz, T., 2017. Ontological Design Futures. Design Philosophy Papers, 15(2), pp.28–40.

Tlostanova, M., 2015. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.