When Architecture Behaves Like a Screen: Reading Outernet London Through Spatial Experience

Through Spatial Experience

You are walking through the city’s centre. The noise folds into light, and the rhythm of footsteps syncs with ads, motion graphics, and music spilling out from large-scale screens. People rush through, some running for a train, others stopping in place as if the city is watching itself through reflections of video and colour.

Groups gather where the brightness intensifies. You were heading west, but the pull of the crowd shifts your direction. Without planning it, you turn too. You step into a building, although it does not feel like one. It is a new kind of interior emerging in global cities. It is neither plaza nor gallery, neither retail hall nor public square. It behaves like a street yet presents itself like a screen.

The space is open, but not neutral. It invites passers-by and spectators, commuters and curious wanderers, and then seems to guide them through a choreography shaped by architecture and programmed media. It is a building that wants to act like public realm and a public realm that performs like an immersive environment. To understand how people navigate this hybrid condition, we need to look beyond the spectacle and into the underlying spatial structure.

A simple question forms:

who is steering this movement? The city, The building, the people, or the screen?

A Hybrid Space With a Commercial Logic

This study examines Outernet London, one of the examples of this emerging typology. It is a privately owned, publicly accessible interior connecting Charing Cross Road with Denmark Street. It stays open at all hours, functioning as part of the pedestrian network. Yet its operation relies on a hybrid commercial model where content shifts throughout the day. Immersive shows run at scheduled intervals, followed by periods of low-intensity visuals, advertising, or brief screen-off transitions while content resets.

These cycles matter. Each type of content shapes a different behavioural atmosphere rather than dictating one. Immersive shows tend to increase density and dwell. Advertising supports the business model. Black-screen transitions often trigger a temporary reset in behaviour.

Architecturally, it is an interior street wrapped in digital surfaces. Behaviourally, it is a testing ground for how media might steer, soften, or redirect aspects of spatial logic. Its publicness is real, but its intentions are shaped by programmed content.

What the Findings Reveal

Over several days across weekday and weekend cycles, I observed how people moved, paused, and gathered inside the Now Building. I spent long stretches standing within the space, often in the same locations as the security staff, who began to recognise me. We spoke occasionally about how the place shifts across the day and how the screens influence the flow of people. These conversations added a grounded sense of how the space feels when you experience it every day rather than only as a visitor or researcher.

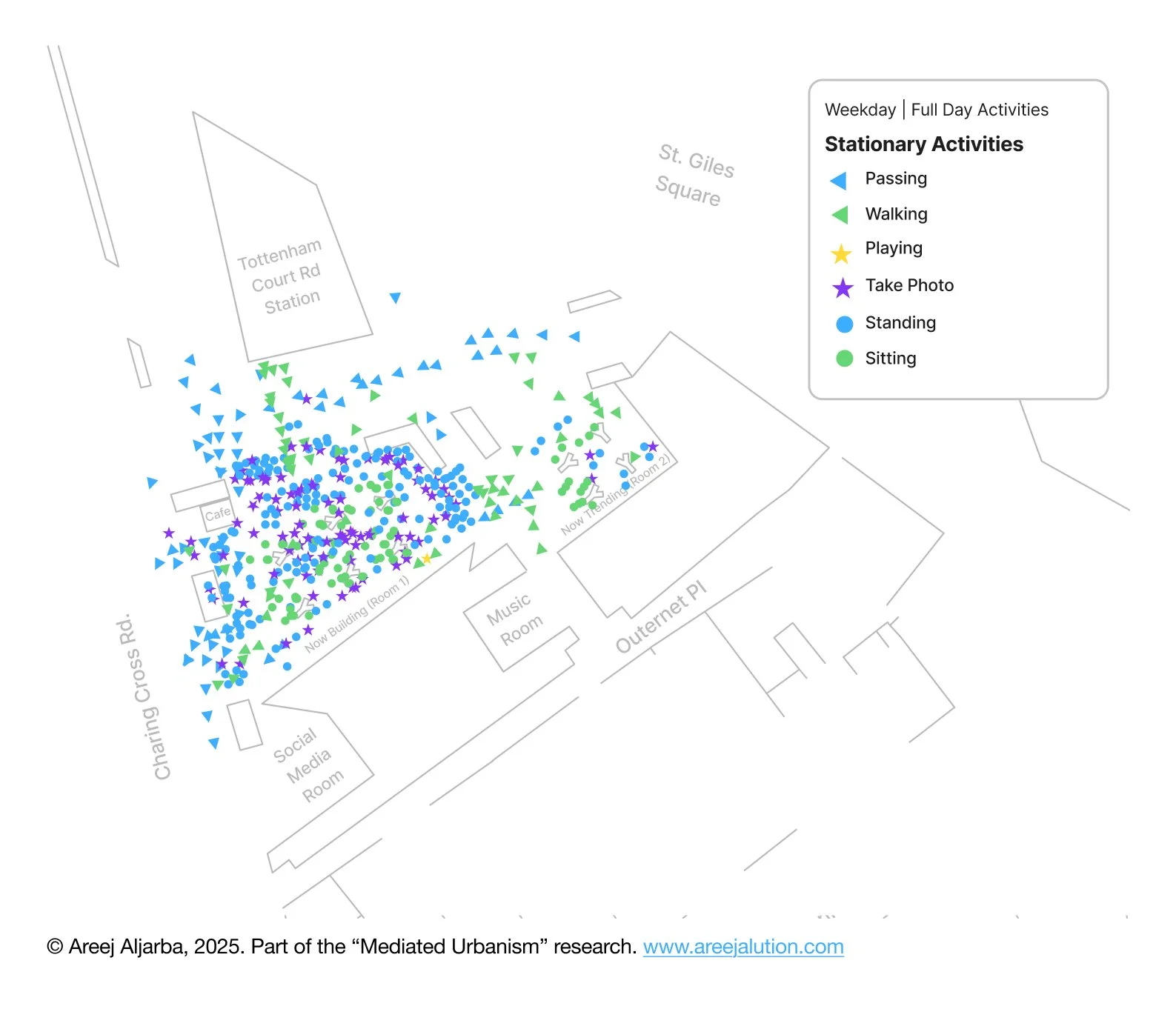

Alongside this on-site immersion, I ran spatial analyses to reveal the underlying logic of the environment. This included segment analysis to understand how the street network channels people into the building; visibility graph analysis (VGA) at two modelling levels, eye and knee height, to see what the space exposes or conceals; and isovist analysis. I also recorded stationary activities, conducted gate counts and in–out flow counts, and mapped trace movements. On the qualitative side, I experimented with using AEIOU in a spatial setting and kept a site diary. Together, these layers helped build a full picture of how architecture and media interact in real time.

Together, these methods revealed patterns that were both predictable and surprising. Spatial configuration provided the structure within which movement unfolded, and digital media tended to intensify or redirect behaviour in ways that felt almost choreographic. The most unexpected insights appeared when space, content, and people collectively shaped the environment at the same moment.

1. Spatial configuration influences fundamental movement

Overlay of weekday total gate counts (summed over all rounds) with segment integration 400m

Segment analysis predicted a strong east to west spine. Gate counts and movement traces confirmed it. Users consistently preferred routes along this spine, independent of media content. Spatial configuration influenced the general tendencies of movement.

Methods: Segment analysis, gate counts, trace mapping

© Areej Aljarba, 2025. Part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research.

2. Digital media temporarily amplifies or redirects movement

When immersive media activated, people were pulled toward the centre of the space. Clusters formed in areas with the highest visibility, and movement slowed as viewers gathered. When the content shifted to low-intensity visuals or advertising, the environment changed. Clusters reduced and movement returned to the core spatial spine. Media did not determine movement patterns. It appeared to intensify or soften existing spatial tendencies.

Methods: Stationary Activities, AEIOU, Trace Movement

Clusters formed in areas with the highest visibility. © 2025 Areej Aljarba. Photographed on-site as part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research study. www.areejalution.com

Content shifted triggered the environment changed. © 2025 Areej Aljarba. Photographed on-site as part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research study. www.areejalution.com

3. Content transitions create release moments

A very consistent pattern appeared whenever the screens shifted content. When immersive programmes ended and the screens briefly went black, or when new content loaded, the space changed instantly. These transitions acted like a signal. People who had been standing or watching dispersed. Movement accelerated. Clusters dissolved, and the space returned to circulation mode.nThe effect was similar to the bell in a school signalling the end of a session. The space shifted from viewing mode back to movement mode.

Methods: Stationary Activities, AEIOU, Trace Movement

The hold and release effect

4. The hold and release effect

Movement traces revealed a recurring behavioural rhythm. People approached along the spatial spine, shifted toward the digital anchor, paused in the centre, then dispersed in multiple directions. This repeated throughout the day and across all content types. It is a choreography of attention shaped by the interplay between spatial structure and digital activation.

Methods: Segment Analysis, Trace Movement, Stationary Activities, AEIOU

5. Segregated edges remain quiet regardless of media activation

Edges with low visibility values did not attract stationary activity. Even strong immersive content did not draw users into the Music Room or narrow southern corridor. These areas maintained quietness as a recurring pattern across conditions.

Methods: VGA, Stationary Activities, AEIOU

© 2025 Areej Aljarba. Photographed on-site as part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research study

6. Thresholds create distinct behavioural modes

Gate A attracted explorers because of its openness and wide visibility field.

Gate C produced rapid passers-by because of low visibility and shallow depth.

Gate G encouraged short social dwell due to proximity to seating and amenities.

These thresholds appeared to support different behavioural tendencies shaped by visibility and spatial cues.

Methods: Isovist, Gate Count, In/Out Flow

7. Spatial identity can override media cues

© 2025 Areej Aljarba. Photographed on-site as part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research study.

Denmark Street consistently attracted a music-oriented demographic, even during immersive shows. This suggests that local cultural identity sometimes plays a stronger role than digital media in shaping behaviour.

Methods: AEIOU, Site Diary

© 2025 Areej Aljarba. Photographed on-site as part of the “Mediated Urbanism” research study.

8. Personas: SPATIAL-Behaviour Profiles

These personas emerged from repeated traces across weekday and weekend observations, combined with gate flows, dwell patterns, and AEIOU notes. They are not demographic categories but Spatial-Behavioural Profiles that I developed to describe how different kinds of users negotiate the same hybrid interior. Each profile reflects recurring patterns in movement, engagement, and spatial choice rather than personal attributes.

Methods: Trace Movement, Stationary Activities, AEIOU, Site Diary

Implications for Future Design

1. Spatial configuration is the design framework

Movement tends to follow spatial logic. Digital layer cannot replace this, but it can enhance or redirect it. Designers need to understand the spatial system before layering digital interventions.

2. Media should be integrated into architectural form

Digital content performs best when it is embedded into logic of space as much as the volumetric and visual structure. It should not be treated as a separate phase. Spatial logic needs to include digital media.

3. Content transitions shape behavioural cycles

Brief black-screen moments or content shifts often act as behavioural cues. These transitions create release moments that disperse clusters and reset the space. Programmers and designers can use transitions strategically to manage density, flow, and rhythms of attention.

4. Thresholds and visibility gradients shape engagement

High visibility entrances support immersive behaviour and exploration. Low visibility entrances encourage rapid passage. Designers can use this intentionally to orchestrate behavioural modes.

5. Edges require distinct strategies

Low visibility edges will not participate in central activity without spatial intervention. Designers can activate them with seating, openness, or improved line of sight. Alternatively, quiet edges can be preserved as intentional retreat zones.

6. Behavioural personas support inclusive and adaptive design

Recognising passers-by, dwellers, and explorers supports planning for varied needs, sensory loads, and comfort. This is where experience design and service design add value, helping choreograph how people transition, pause, interact, or move on.

7. Experience design can bridge media and movement

Hybrid public interiors require careful orchestration of transitions, content rhythm, sensory cues, and spatial affordances. Experience design can ensure that digital media works with, not against, spatial logic.

Closing Reflection

As media architecture becomes more common in cities, understanding how spatial logic and digital layer interact becomes increasingly important. Outernet London shows what happens when architecture behaves like a screen. Movement, attention, and encounter are constantly negotiated between spatial configuration and sensory activation.

Hybrid public interiors are not only spaces of movement or spectacle. They are places where people read space, react to content, and shape the environment through collective behaviour. Studying these dynamics offers a way to design with intention, clarity, and a deeper understanding of public life in digitally mediated cities.