On Reading, Not Recommending

I often get asked by some and recently by junior designers or professional who want to shift careers, what they should read. I struggle with that question, not because I don't read, but because I don't believe reading works well as instruction. Telling someone what to read assumes a shared context, maturity, and set of questions. Those rarely exist.

What I can offer instead is my thinking map. What follows is not a recommendation list. It's a structured snapshot of books I've read throughout my journey and how I organise them for myself. It's also not exhaustive—many influential texts live as PDFs, research papers, or fragments rather than physical books.

This structure is imperfect and evolving, but it gives me visibility into how my thinking has been shaped, stretched, and challenged over time. Think of this less as a syllabus and more as a map you can critique.

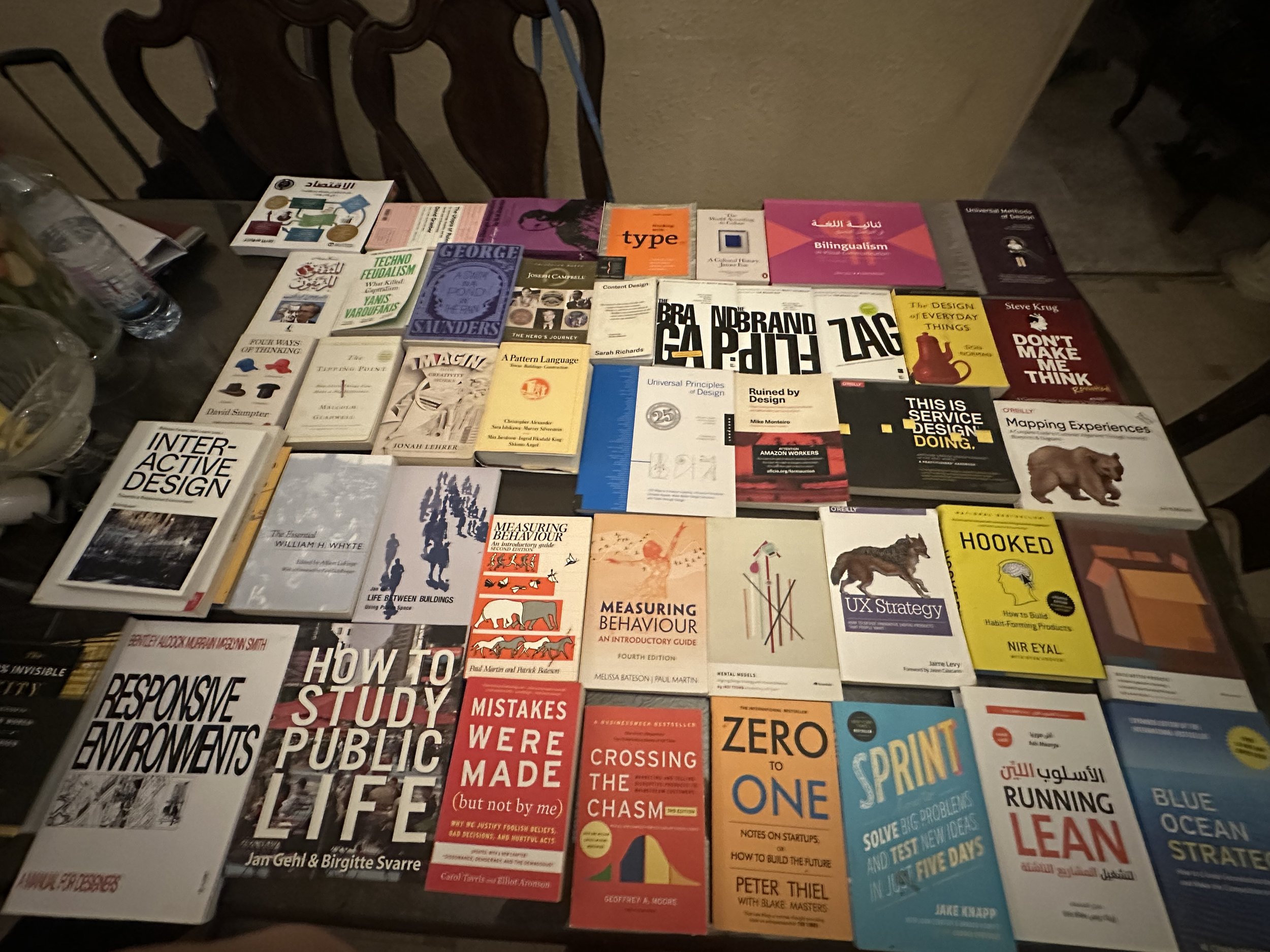

My mom was not happy with this display on her dinning table. But for you here is a snippet of books …

1. Classic Books (Foundational / Rite of Passage)

These books don't teach current practice—they teach how the field learned to see. They're foundational not because they're complete, but because they define the original frame: how interaction design first named its problems, drew its boundaries, and established its intellectual debts.

Books like Don't Make Me Think by Steve Krug, Emotional Design and The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman, and About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design by Alan Cooper shaped my early understanding of interaction as something behavioral, cognitive, and experiential rather than aesthetic.

More formal and research-driven texts such as The Psychology of Human–Computer Interaction by Stuart Card, Thomas Moran, and Allen Newell, Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human–Computer Interactionby Ben Shneiderman and colleagues, and Interaction Design: Beyond Human–Computer Interaction by Yvonne Rogers, Helen Sharp, and Jenny Preece grounded that understanding in theory, models, and academic traditions.

I don't return to these books for tactics. I return to them to recalibrate how I frame problems and what I consider foundational. When I catch myself treating design as pure problem-solving, I return to Norman to remember it's also about emotion, identity, and meaning. When I notice I'm optimizing interfaces without questioning the interaction model itself, I return to Cooper to remember that paradigms matter more than pixels.

These books also act as warnings. Warnings that what was foundational can calcify into dogma. Warnings that disciplines evolve by questioning their origins, not worshipping them.

2. How-To Books (Methods, Frameworks, Activities)

These books give me ways to act, but more importantly, they give me material to think with. Methods aren't recipes. They're structured ways of paying attention, and their value shows up when you know which parts to keep and which to discard.

Books such as Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior by Indi Young set foundational ground for me on how to define my unit of analysis and identify the focus of study, while Measuring Behaviour by Bill Albert and Tom Tullis taught me which behavioral metrics to track, how to measure them reliably, and what those measurements can and cannot tell you. Books like Universal Methods of Design and Universal Principles of Design by William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, and Jill Butler give me a repertoire of methods and concepts that enrich my approach—experimental methods I play with, adapt, and test in different contexts.

Then there are practitioner guides like This Is Service Design Doing by Marc Stickdorn and Jakob Schneider and Mapping Experiences by Jim Kalbach. You read these to see how other practitioners actually do what they do—their workflows, their tools in action, their real-world adaptations.

The most foundational books in this category for me were Contextual Inquiry and Contextual Design by Karen Holtzblatt and Hugh Beyer, and UX Strategy by Jaime Levy. These offer comprehensive structures for inquiry, synthesis, and decision-making that underpin much of how I approach research and strategy work.

I don't use these books as recipes. I use them as material—things to adapt, combine, or discard depending on context. Their value lies less in correctness and more in what they make visible. A good method reveals patterns you wouldn't have noticed otherwise. A bad method applied thoughtfully can still generate useful friction.

What separates craft from procedure is knowing when a method stops serving inquiry and starts performing rigor for an audience. These books taught me frameworks, but practice taught me when to break them.

3. Skills Books (What Complements My Core)

If foundational books taught me to frame problems, and methods taught me to act on them, skills books taught me something else: how to operate inside constraints that aren't primarily about users or interfaces.

Some help me operationalise my work inside organisations. Books like Sprint by Jake Knapp, Lean Approach, Testing Business Ideas by David J. Bland and Alexander Osterwalder, Business Model Generation and Value Proposition Design by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur, and Build Better Products: A Modern Approach to Building help translate research and systems thinking into action under real constraints—time, politics, competing priorities, and organizational inertia. I don't necessarily agree with all of them—in fact, I question many critically—but reading them gives me organizational language. Some of these became trendy in certain organizations, and knowing their vocabulary helps me navigate, challenge, or translate ideas in those contexts.

Others support the visual, linguistic, and expressive dimensions of my work. Type by Ellen Lupton, The World According to Color by James Fox, Content Design by Sarah Richards, and books on bilingualism sharpen how I think about legibility, perception, meaning, and cultural translation. These aren't decorative skills. Language and visual form are infrastructural—they determine what can be understood, by whom, and under what conditions.

Then there are books that support judgment and self-awareness. Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me) by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson, Imagine: Creativity by Jonah Lehrer, Four Ways of Thinking, and A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders all contribute to how I think, reflect, and work through ambiguity. They matter because design decisions are rarely between right and wrong—they're between competing goods, and judgment is what separates a defensible position from an arbitrary one.

These books don't define my core practice. They make it possible to sustain it in environments that aren't designed for depth.

4. Advanced / Opinionated Books (Pioneers, Provocations)

These are books with strong positions—some genuinely innovative, others more provocative than sound. What matters isn't whether I agree with them wholesale, but that they're influential and shape how organizations think.

Ruined by Design by Mike Monteiro, Blue Ocean Strategy by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey A. Moore, Zero to One by Peter Thiel, Hooked by Nir Eyal, and The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell have all contributed something valuable—whether that's a genuine innovation in thinking, a useful framework, or simply a compelling narrative that moved conversations forward.

But they also require critical engagement. Some carry embedded assumptions about markets, users, value, and what counts as innovation. Some became popular precisely because they simplified complex problems into memorable frameworks. Reading them isn't about wholesale adoption or rejection, it's about understanding what language is circulating in boardrooms, what metaphors are shaping strategy, and what unexamined beliefs are baked into "common sense" business thinking.

I need to know these books because I need to know what vocabulary decisions are being made in. Otherwise I'm designing in one language while strategy happens in another. Critical reading here means engaging with both what these books innovated and what they oversimplified or left unexamined.

5. Nearby Fields

Many of the problems I work on don't belong to design alone, so neither does my reading. These books come from architecture, anthropology, urban planning, branding, and geography fields that share more with design than their disciplinary boundaries might suggest.

Architecture and design, for instance, share fundamental concerns: pattern, structure, navigation, experience, and meaning-making. Although these domains may not always talk directly to each other, books like A Pattern Languageby Christopher Alexander contributed significantly to information architecture, while The Image of the City by Kevin Lynch established foundational concepts: legibility, wayfinding, cognitive mapping that transfer directly to interface and information design. Branding is often associated with UX, and that connection becomes even more explicit when we move into customer experience (CX), where brand, service, and interaction converge something explored in Marty Neumeier's books like Zag, The Brand Gap, and Brand Flip.

Books such as Visual Anthropology: Essential Method and Theory by Fadwa El Guindi and The Anthropology of Digital Practices by John Postill helped me sharpen cultural lenses and qualitative methods for observing behavior in context. The 99% Invisible City by Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt taught me to decode urban surfaces and structures, treating urban form as an interaction system that reveals hidden power encoded in everyday design. Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities by Alain Bertaud provides a counterbalance a framework for understanding cities as emergent systems shaped by decentralized choices, constraints, and market forces rather than aesthetics, ideology, or top-down plans.

These books feed my interdisciplinary, sometimes transdisciplinary, mind and creative process. They help me see patterns across domains, borrow methods from one field to solve problems in another, and recognize when a design problem is actually an anthropological, spatial, or branding question in disguise. This kind of cross-pollination often leads to innovation because it breaks the inherited assumptions of any single discipline.

These books rarely give me answers. They give me better questions and often, they reveal that I've been asking the wrong question entirely. When I'm stuck on an interface problem, the breakthrough usually comes from a shift in framing, and that shift often comes from a field that doesn't care about interfaces at all.

6. Seemingly Random Interests

This category is intentional, even if it looks scattered at first glance. Here I read about the large, often invisible systems that operate in the background of everything else: economics, bureaucracy, institutions, media, and power. These are not peripheral to design or research. They are the conditions under which design operates.

I might start with basic economics texts an "economy 101" level of understanding and move toward more contemporary critiques like Technofeudalism by Yanis Varoufakis. Economics, for me, is not about markets in the abstract; it's about understanding what actually runs behind the scenes. Having even a working literacy here separates you from being a pure doer. It gives you a way to reason about constraints, incentives, and systemic consequences rather than treating them as external forces.

Books like The Utopia of Rules by David Graeber are particularly important because they challenge an assumption that quietly underpins much of design, planning, and computational thinking: the idea that better rules, better interfaces, or better models automatically produce better outcomes. Graeber exposes how bureaucracy, rationalisation, and procedural logic can just as easily generate friction, absurdity, and harm.

I also read books in this category, such as The Fake Intellectuals: The Media Triumph of Experts in Deception by Pascal Boniface or Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber—not necessarily for their specific arguments, but for what they train me to notice. They act as warnings. Warnings that design, data, and systems can easily become bullshit-job generators. Warnings about how media logic distorts "knowledge that looks scientific." Warnings that sharpen epistemic vigilance in interdisciplinary work, especially where persuasion, authority, and expertise are involved.

The value of these books rarely shows up immediately. It appears later, influencing how I think about institutions, incentives, bureaucracy, legitimacy, and systemic behavior—often at the moment when a project risks becoming elegant, persuasive, and wrong.

7. Your Niche (Still Forming)

This is the least stable category, and that's deliberate. A niche isn't found: it's built… slowly, through questions that refuse to resolve and problems that keep reappearing across different contexts. These books sit here because they're helping me construct something, not because I've figured out what it is yet.

Some of these I've read deeply. Others are still on my to=read list. I'm including them here not to give the impression I've mastered everything mentioned, but because they're part of the constellation I'm actively orienting toward books that feel like they belong to the same question, even if I haven't fully engaged with all of them yet.

Books such as Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and Future Systems V edited by Tareq Ahram and Redha Taiar, Speculative Everything: Design Fiction and Social Dreaming by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Responsive Environments: An Interdisciplinary Manifesto on Design, Technology and the Human Experience by Allen Sayegh, Stefano Andreani, and Matteo Kalchschmidt, Space Is the Machine by Bill Hillier, Life Between Buildings by Jan Gehl, How to Study Public Life by Jan Gehl and Birgitte Svarre, The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, and The Dialogic Imagination by Mikhail Bakhtin sit together because they point toward questions I'm still actively working through.

Space Is the Machine, for example, could easily belong to foundational texts, but it sits here because the spatial lens it introduced became central later in my journey not as background knowledge, but as a live question about how environments structure possibility. How to Study Public Life could belong to methods, but for now it lives here because it's helping shape my niche rather than just my toolkit. It's teaching me to see interaction as situated, embodied, and spatial, not just cognitive or digital.

As my thinking evolves, some of these books may migrate to other categories. Others may fade. The point isn't to stabilize this category it's to keep it generative. A niche that stops evolving becomes a silo, and silos are where thinking goes to calcify.

What holds these books together isn't theme or method it's an orientation toward questions about interaction in public, spatial, and systemic contexts that can't be answered with screens alone. Whether this becomes a coherent practice or remains productive confusion matters less than staying in the tension long enough to find out.

How can you use this Reading thinking Map?

Questions to map your own reading whatever you are reading or trying to specialise in. These categories emerged from my practice, but the underlying questions can transfer to any field:

What texts define how your field originally framed its problems? Not what's currently fashionable, but what established the intellectual frame you're either building on or reacting against?

What gives you structured ways to pay attention? What helps you see patterns, generate insights, or make decisions and which parts of those methods do you actually use versus perform?

What knowledge sits adjacent to your core practice but makes it possible to sustain? What helps you translate your work into organizational language, communicate across difference, or maintain judgment under pressure?

What books shape the dominant narratives in your field, even if you disagree with them? What language is circulating in decision-making spaces, and do you know it well enough to challenge or translate it?

What fields share your concerns but approach them differently? Where might a shift in framing, borrowed from architecture, anthropology, economics, or elsewhere unlock a problem you've been stuck on?

What larger systems (economic, institutional, political, media) create the conditions under which you work? Do you understand them well enough to recognize when they're shaping your work invisibly?

What questions keep reappearing across different contexts? What are you actively building toward, even if you don't know what it is yet

Lessons learned

A few things I wish I had done differently:

I wish I had kept a simple Airtable or Notion database of what I read, why I read it, and what it changed in my thinking, not to optimise reading, but to increase visibility. To see where I was over-indexing, where I needed to read more, and where to branch next. Reading leaves traces, but without deliberate capture, those traces fade faster than they should.

I've also learned that reading in PDFs doesn't work well for me. I tend to lose the files and engage less deeply, even though PDFs can be powerful for digital analysis and annotation. This will be different for others. What matters isn't the format, it's knowing which formats support your actual reading behavior, not your ideal version of it.

And finally, reading reviews before buying helps. This sounds obvious, but I've been notorious for buying books on a whim. Pausing to see how others actually engaged with a book not just what they thought of it, but what they did with it—often saves time and disappointment.